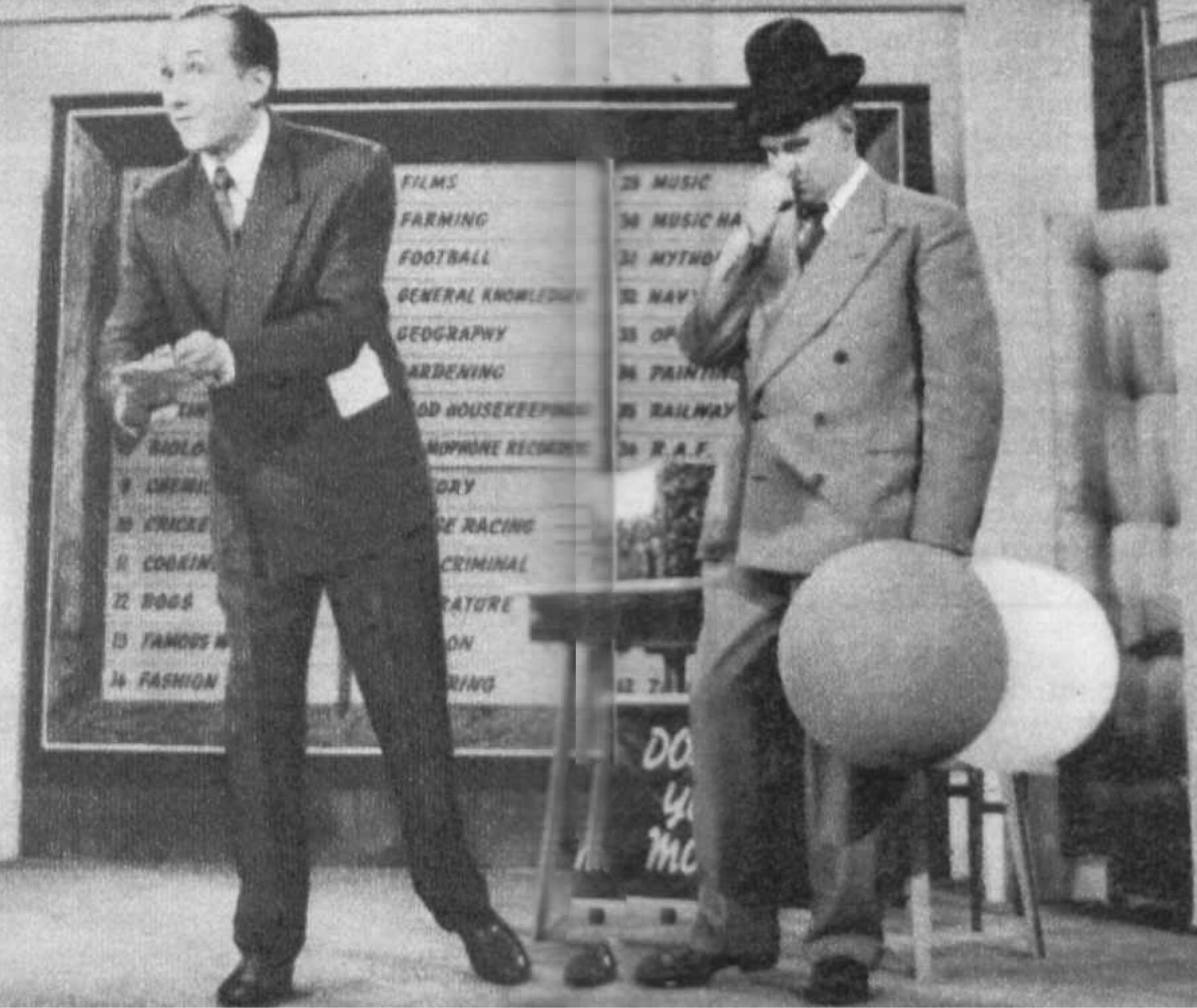

HE was large, fat and jolly. He shook with laughter as he stood beside the microphone. Then quizmaster Hughie Green asked him: “What’s your job?” “You’ll never believe me,” said the fat man.

“Go on,” said Hughie Green. “I’m a morgue attendant,” said the fat man and roared with laughter. The audience couldn’t help itself and roared too.

Then there was the girl who when asked: “Are you married?” answered “No — I live at home with two sisters and a b— of a brother.” “A piece,” says Hughie Green, “that ended up on the cutting room floor.”

The same girl, asked what questions she wanted to take, replied: “On cooking.”

“Well,” asked Hughie, “what kind of sauce do you put on the following meats — chicken?” “Mint sauce,” she replied “No, I’m sorry that’s wrong,” said Hughie. “What about pork chops?”

“Mint sauce,” she said.

“But you don’t put mint sauce on pork chops,” protested Hughie.

“Well, we do on our b— pork chops,” she said.

It was the summer of 1955 and Hughie Green was telerecording the first of his famous Double Your Money quiz shows—one of the longest running shows on television.

The search for programmes by the new Independent Television companies was well under way four months before the service opened on September 22, 1955.

It was towards the end of May that an Associated-Rediffusion talent scout called at the Baker Street studios in London where Hughie Green was recording the radio version of his show for Radio Luxembourg.

“Would you like to try it for TV?” asked the talent scout.

“Would I?” said Hughie. “The answer’s ‘yes’.”

“I realised,” he says today, “what wonderful opportunities ITV was opening up for everybody in the entertainment and allied fields and I knew I’d have to be in it. We telerecorded a show and in less than a month Associated-Rediffusion had made up their minds to buy it.

“It was pretty tough doing them in those early days. Sometimes we were stuck for an audience. I remember one night only a handful of people turned up for some reason or other. So, even though we had makeup on our faces, all of us, including myself, went out into the streets and knocked on people’s doors and asked them if they would like to take part in a TV show. And that way we got a very good mob.

“Telerecording was fairly primitive in those days. The cameras could only shoot 10 minutes or so of the show at a time. You’d have got everybody warmed up and somebody would be about to say something funny, or somebody’s trousers would be about to fall off, when the cameraman would call out: ’The film’s run out.’

“So you’d swear at him, hate him and shout how you loathed the system and so on — and wait until he had re-loaded.”

Elsewhere, staff training was carried out at a furious pace.

Ex-BBC men like Stephen MacCormack and Barry Baker, men who had just started in television like ex-navy man Commander Robert Everett, were flown to New York to study how American commercial TV dealt with the tricky technical job of timing programmes and commercials.

At the small Viking Studios off Kensington High Street, two training courses with cameras and equipment were run for all the programme staff.

Directors, secretaries, sound mixers, vision mixers, lighting experts, cameramen — all listened to lectures and then tried out in practice what they had been taught. Alongside them, auditions for announcers, “personalities,” actors and actresses, were conducted on closed circuit television.

“I had to audition the announcers,” says Leslie Mitchell. “Anybody and everybody thought they could do it. Some were very nearly right: some were terrible. I think I must have auditioned about 300 people altogether — but it seemed like 3,000.”

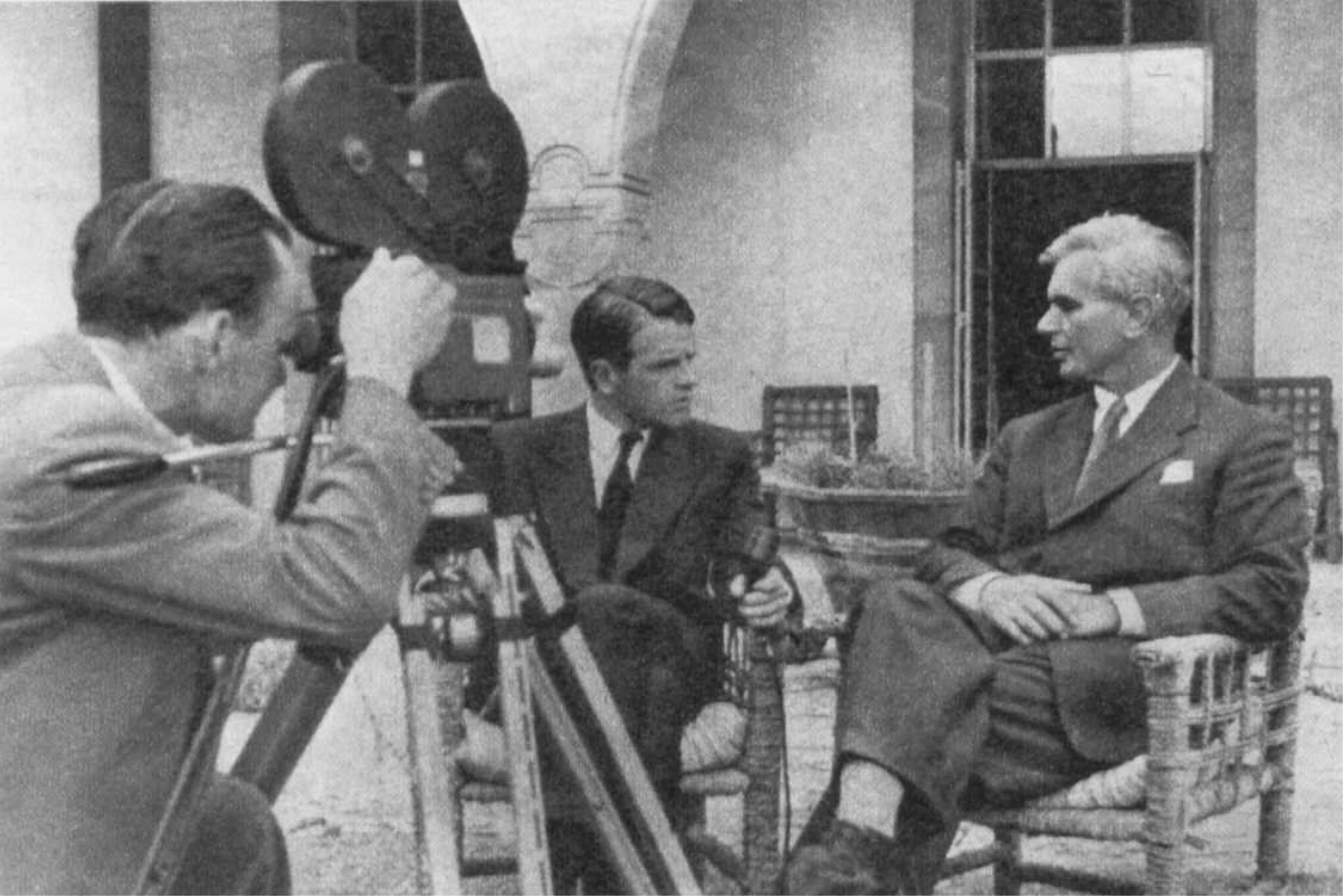

In ITN, Chris Chataway and Robin Day stumblingly learned to read news bulletins. “My most vivid memory,” says Chataway, “is of this wooden board which was put up to simulate a TV camera, into which we solemnly delivered these news bulletins. We would crane forward and talk into this wooden framework while everybody stood around and watched.

“Then we were taught how to conduct an interview. People forgot that the standard BBC interview in those days consisted of a reporter almost on his knees at the bottom of airport steps, saying: “How do you view the current situation, sir?” and taking the answer without once interrupting.

“I remember when the editor told me to interview Field Marshal Harding. ‘What will you say to him?’ he asked me.

“I thought I’d ask ‘how do you think things are developing in Cyprus, sir?’ ‘Whatever you ask him,’ said the editor, ‘don’t say: sir’.”

By this time Television House had become known affectionately as “The Hellpit.” Pneumatic drills chattered all day long. Carpenters and bricklayers worked alongside producers and directors. There were hazards and mysterious happenings.

“I had a desk at a window overlooking the well of Television House,” says drama director Cyril Coke. “One day I lifted my telephone to make a call. But the phone had gone dead. I rattled it once or twice but it stayed dead. So I crossed the office to another desk and began to dial from the extension there.

Suddenly, an enormous piece of steel girder came crashing down from the top of the building. It bounced off some projections, shot through the window on to the desk which I had just left.

“If I’d still been sitting there, almost certainly I’d have been killed. But the really extraordinary thing was when the phone people checked my extension, there was nothing wrong with it — it ought to have worked perfectly!”

The chaos and difficulties of working in Television House in those days is described by Eric Linden, features editor of TVTimes who remembers: “I used to go along there from the offices of TVTimes, then in Gough Square, to find out who people were and where they were. I remember checking with security man Glyn Davies to try to put names to people but he was just as baffled as anybody.

“It was quite easy in those days for anybody to walk in and out the place, in fact, one day he discovered two men occupying an office in Television House and using the phones to carry on a business. Neither had the slightest right to be there — they were just two strangers who had availed themselves of the conditions.”